I chose the hotel in Milan for my first stop because it is near the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan’s major historic art gallery. The building site was originally a convent but changed over the years to an academy for arts and architecture. The palazzo or palace main building was constructed in the 17th century, neo-classical style, and the site has also houses an observatory, library and extensive gardens.

I pre-booked admission for 9 am to give me lots of time to view the collection. The space occupied by the Pinacoteca di Brera is not enormous compared to the Louvre or National Gallery in London. The original space has been extended but is still physically manageable. But there are important works in the collection so there’s lots of reasons to pause and contemplate.

The art collection was started by Napoleon, a common theme in northern Italy. Cynthia Saltzman’s book, Plunder, focuses on the theft of Veronese’s painting “Feast in the House of Levi” from Venice by Napoleon during his conquest of most of Italy and most of Europe, for that matter. The book also describes how Napoleon was helping himself to art and artifacts from all the areas of Europe and Africa that he conquered.

From his purloined art, Napoleon started the Louvre and also the collection now in the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. His statue in the courtyard was by Canova, considered one of the greatest artists in Europe at the time.

What makes less sense to me is that after Napoleon’s defeat, instead of returning the art from whence it was stolen, a committee decided where to put the art instead of returning all of it. It seems it was thought that some areas should share their cultural wealth. I guess it’s a good excuse for art historians to ask to travel around extra to look at art work but it does make me scratch my head in wonder why works specific to a particular place now reside elsewhere.

Gentile Bellini, for example, has an important painting about Venice on display in Milan.

One of Tintoretto’s most important works about St Mark, the patron saint of Venice, is also in Milan.

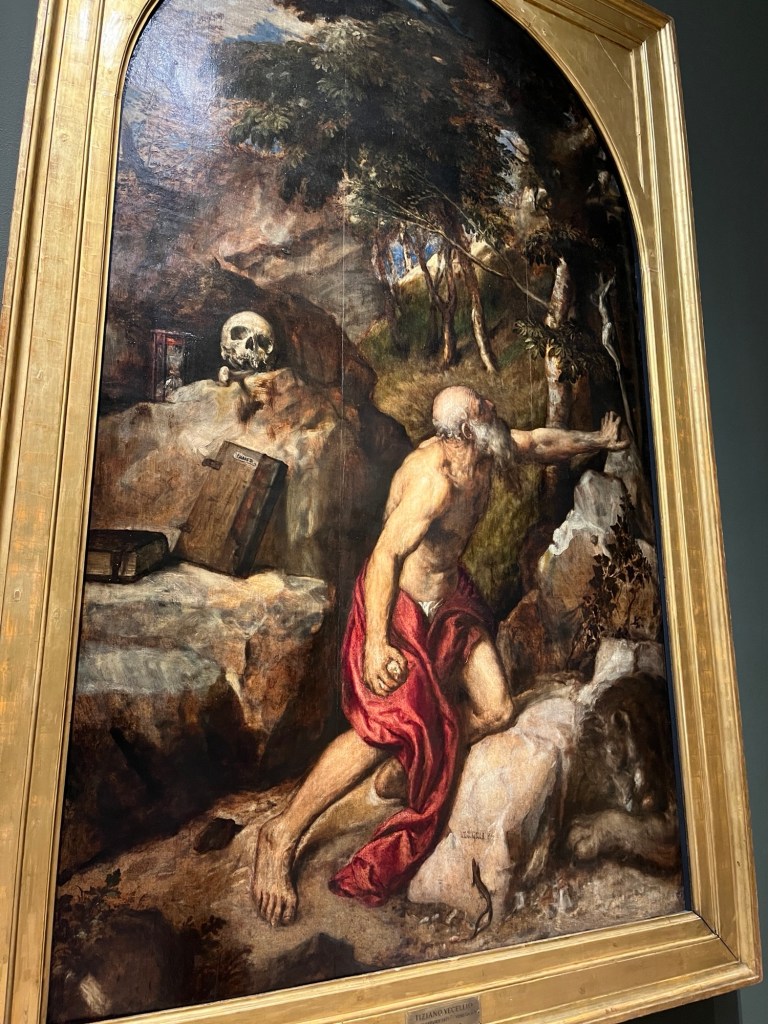

Every important museum needs a Titian as well:

And to complete the triumvirate of great Venetian artists, there’s also a Veronese “Last Supper”:

Great museums also need a Raphael:

A Rubens:

None of the above were originally in Milan.

I really wanted to see the Brera’s Caravaggio, his second version of “Supper at Emmaus”. At least this was painted not too far from Milan and Caravaggio was born in Milan and his familiar name of “Caravaggio” is a town near Milan.

It’s believed to be the first painting he completed after killing Ranuccio Tomassoni while he was in hiding. Some of the brushstrokes look quick. And some of the paint appears to be so thin the under painting is starting to show. What is on the platter being held by the woman?

The Caravaggio is on display in a room where there are a number of paintings by the Carracci, the family of Baroque painters from Bologna. The Milanese family that owned the paintings had financial problems so sold their collection to the Italian government who in turn gave it to the Brera.

The Brera also received and acquired a number of 19th century works with themes related to the Risorgimento, the Italian unification movement. Francesco Hayez is probably Milan’s most famous artist who supported the Risorgimento. His statue is in the small garden by the Brera entrance, the first photo in this post. Hayez (whose name doesn’t sound Italian because his father was from France), was a painter in the Romanticism movement. His most famous painting is “The Kiss”.

According to the Brera, the man is wearing red, white and green, like the Italian flag, and the woman is in white and blue, like the French flag as French troops were supporting the Savoy troops fighting for Italian unification. I could not see any green but it was painted around 1859 so maybe the colour has faded.

I also wanted to look at Mantegna’s “Dead Christ” or “Lamentation of Christ”.

The painting is remarkable for its extreme foreshortening. Mantegna was so good at perspective he could use it for unusual points of view. This was done in the early Renaissance around 1480 when some lesser artists had yet to figure out the basics of mathematical perspective.

Piero della Francesca, who was at least a few years older than Mantegna (no one knows when he was born), was one of the first to figure out mathematic perspective. In fact, Piero, as a mathematician, painted to demonstrate mathematical principles. His “Madonna and Federico da Montefeltro” or “Sacre Conversazione” was painted around the 1470s. Almost everything about dates for Piero and his works are uncertain.

This is what the Brera says about this work:

After the Napoleonic abolitions, the altarpiece came to Brera from the church of San Bernardino in Urbino, erected by Federico da Montefeltro to house his own grave. It is possible, but not certain, that the picture was originally painted for this location, and for the duke’s tomb. The interventions of restoration and recent studies have confirmed that the size of the work has been reduced and that the artist had intended the architecture to be more spacious and airy, with the figures gathered under the huge lantern of a dome. Despite the mutilation it has undergone, the work constitutes an exemplary result of the perspective research conducted by Central Italian artists in the late 15th century.

The iconography is that of the Sacra Conversazione: at the center the Virgin is seated on a throne, holding the sleeping Child; around her are arranged, from the left, St. John the Baptist, St. Bernardine, St. Jerome beating his breast with a stone, St. Francis displaying the stigmata, St. Peter Martyr with the wound on his head and St. John the Evangelist. Behind them we see the archangels and, kneeling in front of the sacred group, Federico da Montefeltro in the dress of a military commander.

In the altarpiece the private history of the client is intertwined with religious devotion and the public – and therefore political – purpose for which it was conceived, creating an image whose significance is still debated by scholars today.

It is likely that Federico commissioned it after the birth of his heir, followed by the death of his wife Battista Sforza (1472), and that he wanted to underline the protection granted by the Virgin to his own dynastic authority through this work dense in symbols. It may no longer be possible for us to fully understand their meaning: for example, the ostrich’s egg represents the miraculous maternity of the Virgin but is also a heraldic emblem of the Montefeltro family; the sleeping Child alludes to maternity and at the same time to death, supporting the hypothesis of the funerary destination of the work.

The rain forecast never materialized so I thought I should go to a bookstore as well as look at the Duomo. So many tourists in that area of Milan, less than 10 minutes from the Brera.

La Scala is under wraps.

Piazza del Duomo

I decided to check out the rooftop terrace of this hotel since it wasn’t raining. The view is more of modern Milan.